- ”” ”History & Heritage”

- ”” ”Killagholehane”

- ”” ”Useful Information”

- ”” ”Directions”

- ”” ”Accommodation/Restaurants”

- ”” ”Gallery”

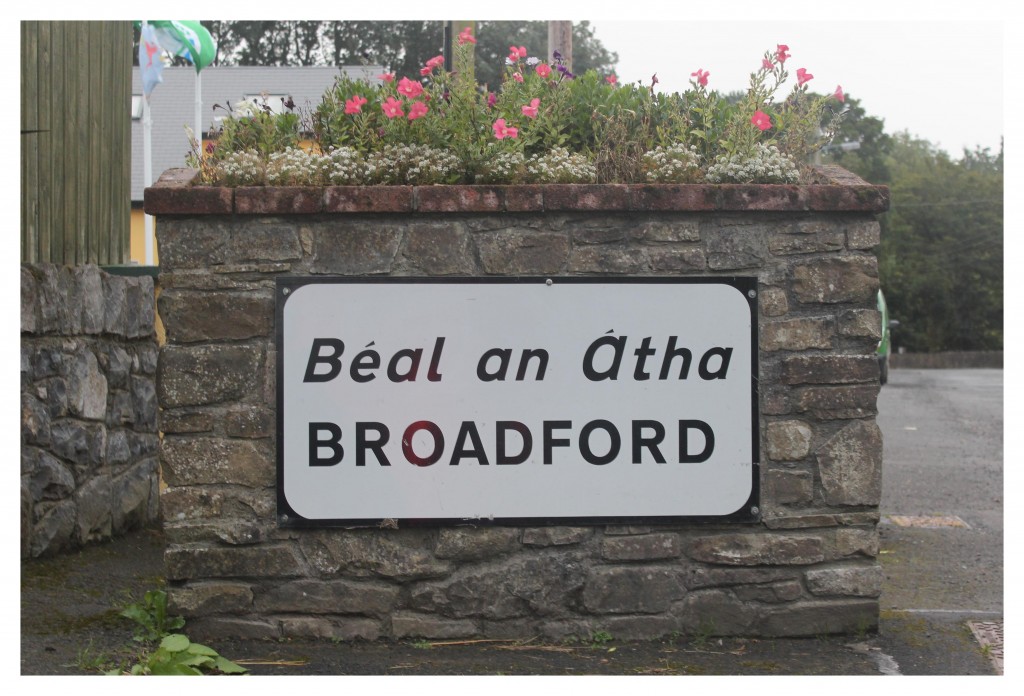

“Thiar le hais an droichid ceathrughadh míle as so – bhí an chéad Béal an Átha suidhte. Is fuirist tuiscint conus a fuair an áit a hainm. Tá rían an Átha le hais an droichid fós ann. Agus an “béal”, tá sé soiléir go leor mar oscluigheann an abha amach i bhfuirm béil ag an bpoinnte seo. Sin bunús na h-ainmne ‘Béal an Átha’”

“Back beside the bridge, a quarter of a mile from here, the first Béal an Átha was located. It is easy to understand how the place got it’s name. A trace of the ford beside the bridge still exists. And the ‘mouth’ – it is obvious enough because the river opens out into the shape of a mouth at this point. That is the origin of the name ‘Béal an Átha.’”

Séamus Ó Gruagáin, Principal Teacher, Broadford National School, The above is taken from ‘The Schools Manuscript Collection, 1937/1938’

The Ordnance Survey map of 1841 shows a newer village running from the old road to Tullylease as far as the quarry (arboretum) and as far as the Church on the opposite side. The map shows a much older village running from Broadford bridge to Pierce’s fort. 5 limestone quarries were being worked near the village at that time and the Mohilly family were famous stonemasons. Their craftsmanship is to be seen in many of the nearby cemeteries.

The 5 conjoined houses which centre on the Post Office and contribute so much to the architecture of the village were built by Henry Dean Spread in the early 1880s. In 1954, eight new houses, (St. Mary’s Terrace), were constructed by Limerick Co. Council. The next development began in 1979/80 with the construction of John Paul Terrace. The development of the village on the Newcastle West road continued with the construction of community housing named Curramore in the year 2000.

The sculpture, beside this storyboard, was erected in 1998, dedicated to the memory of Dáibhí Ó Bruadair, the 17th century bardic poet to the Fitzgeralds of Springfield Castle.

”Catholic Church”

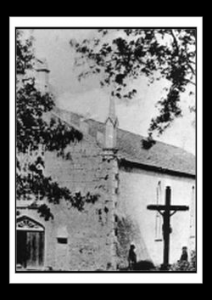

The first post Reformation Catholic Church was built in 1819/20 on the Newcastle West road where Ó’Suilleabháin’s corner house now stands. This was replaced by the present day church Our Lady of the Snows in 1844.( Fr. Patrick Quaid, P.P.) It measured 90 feet by 30 feet. The belfry was added in 1856. The porch, front wall and gates were added by Canon O’Connor, P.P. in the 1950s. Extensive renovations were carried out in 1983/84.

The first post Reformation Catholic Church was built in 1819/20 on the Newcastle West road where Ó’Suilleabháin’s corner house now stands. This was replaced by the present day church Our Lady of the Snows in 1844.( Fr. Patrick Quaid, P.P.) It measured 90 feet by 30 feet. The belfry was added in 1856. The porch, front wall and gates were added by Canon O’Connor, P.P. in the 1950s. Extensive renovations were carried out in 1983/84.

”Primary Education”

The first National School was opened in 1837 and in the first year had 129 pupils. It was replaced in 1870 on the same site. When a new school, Scoil Mhuire, was opened in 1963 the old school was renovated and opened as the present Community Centre.

”Trades & Business In The Past”

According to the 1901 census there were 10 shops, 2 bakeries, 2 victuallers, 2 tailors, 2 dressmakers, 2 blacksmiths, 1 shoemaker, 4 coach builders, 1 draftsman/surveyor, 1 carman, 4 teachers, 1 road contractor, 2 coopers, 1 milliner and 1 creamery manager in Broadford. By this time the village had also acquired a Post Office, a Dispensary and a Constabulary Station. A creamery was established in 1889 and was the main source of industrial employment following the demise of the quarries. The creamery ceased milk intake in 1992. The creamery store continued in business until 1997. The original handball alley which dated back to the 1880s was located where the Millennium Garden now stands. The new handball complex is situated on the western end of the village. By 1950 there were 2 drapers, 5 grocery shops, 2 bakeries, 1 grocery/hardware shop, 4 grocery/wine and spirit merchants, 1 bicycle shop, 2 blacksmiths, 2 harness makers, 2 shoemakers, 2 tailors, 4 dressmakers, 3 coopers, 2 carpenters, 1 coachbuilder and a Post Office in Broadford village.

”Today”

Today Broadford village has grown into a thriving community with a number of businesses, voluntary community organisations and sports clubs.

”Cillin”

Cilliní – Remembering the Forgotten

On September 23rd 2018 Broadford Ashford Walking Trails Committee organised a walk commemorating the people interred in the Cillín burial ground in Killilagh. A plaque was unveiled in the Millennium Garden in Broadford. The plaque is a marker intended to give a respectful acknowledgement to the unnamed. It reads:

Remembering the Families buried in the Cillín & Famine Burial Ground at Killilagh (3km west of here). For centuries the Cillín has been the final resting place of unbaptised infants & also victims of the Great Hunger.

“In silent need they searched for Hallowed ground & found a place to lay their children down”

In memory of these countless souls known only to God.

Ar dheis De go raibh a n-anamacha

A Commemorative booklet was printed and distributed on the day. In included the following article giving the history of Cillíní in general and the Cillín at Killilagh in particular.

Separate burial for unbaptised infants’ dates back thousands of years in Europe. As far back as the 5th century, St. Augustine considered the souls of the unbaptised as marked with the stain of original sin and so could not enter heaven. They were condemned to Hell. In the 12th century, a new belief developed, that the souls of the unbaptised were separated for eternity in Limbo – a purgatorial state of no pain between Heaven and Hell.

In Ireland, the use of separate burial plots for unbaptised infants is believed to have begun sometime in the 16th century. The Church at the time ruled that the mortal remains of infants who died before receiving the sacrament of baptism were forbidden from burial in consecrated ground. This separation in burial represented their separation in the afterlife. The same separation was applied to women who died in childbirth and for those who died by suicide. Murderers (and sometimes their victims), heretics, strangers to an area and shipwrecked sailors were also forbidden from burial in consecrated ground.

Despite having lost in the region of 20-40% of its population due to the Irish Confederate Wars and famine from 1641-53, Ireland’s population doubled during the 17th century from around 1 million to two million people. However, like other European countries, there was a high infant mortality rate with up to a quarter of babies dying before their first birthday. Maternal mortality rates were also significant – in the region of 1000 maternal deaths per 100,000 births. Poverty, malnutrition and lack of medical care being the most prevalent reasons for such a high rate of mortality. For this reason, it became custom for babies to be baptised as quickly as possible (usually within 24 hours) after birth to ensure the child’s soul went to Heaven in the event of an early death. However, salvation in the form of baptism could not be achieved where the child was stillborn. Therefore, Cillíns such as that at Killilagh became a necessity of Irish life. Cillín on translation from Irish means “little cell” or “little churchyard” thought to be derived from the latin cella meaning “little church”. It is a word that is commonly found in its English form “Killeen” in place names across the country.

The location of many Cilliní across the country are simply unknown due to the secrecy that surrounded their use. Sites were chosen for varying reasons with symbols apparent from Irelands pagan and Christian beliefs. A high proportion, including that of the Cillín in Killilagh, were either in, or, as close as possible to consecrated ground. Throughout the country, Cilliní can be found near abandoned church ruins, holy wells, ringforts as well as lands adjacent to churches and graveyards. In some cases, stones were removed from graveyard walls with the infant’s remains being placed inside and the stones carefully replaced. Killilagh, with its ruins of a 14th century church must have been chosen for its former consecrated status. Also, there are some pre-Christian symbols apparent with the location. The site is by running water, which reflects the belief that spirits cannot cross water. The location is also triangular in shape, which reflects a once held belief that a spirit cannot move out of a triangle. In addition, patterns have been seen where Cilliní are placed at the edge of parishes and near crossroads. Again, we see these features in Killilagh. While the exact reasons for the selection of these burial sites will never be fully understood, it seems that they were located on sites that were unlikely to be disturbed in the future.

The custom associated with burial in a Cillín was that it took place in secret without ceremony between the hours of dusk and dawn. Only a male family member usually the infant’s father sometimes accompanied by a grandfather performed the burial. The mother was not allowed to be present and the child was not spoken about afterwards. Those parents were burdened by the belief that they would never see that child in Heaven. The second Vatican Council of the Catholic Church (1962-1965) softened the churches position and concluded that the souls of the unbaptised could enter Heaven. With that, a funeral rite for the unbaptised became practice from 1969 rendering the use of Cilliní no longer necessary. In 2007, Pope Benedict effectively abolished Limbo from Catholic teaching following a theological commission study, which concluded that it was an “unduly restrictive view of salvation”.

During An Gorta Mór, as the local graveyards began to fill at alarming rates, it became necessary for the Cillín in Killilagh to be reopened as the final resting place for victims of that humanitarian crisis. It is not known how many infants or famine victims are buried in Killilagh and folklore has it that “a man of the roads” was the last person to be buried in the Cillín in the 1930’s.

Actively used in the first half of the 20th century, Cilliní are a part of living memory for many people. It is hugely important that they be marked and remembered by future generations.

Corina Sheedy

”Quarantine”

Quarantine by Eavan Boland

In the worst hour of the worst season

of the worst year of a whole people

a man set out from the workhouse with his wife.

He was walking — they were both walking — north.

She was sick with famine fever and could not keep up.

He lifted her and put her on his back.

He walked like that west and west and north.

Until at nightfall under freezing stars they arrived.

In the morning they were both found dead.

Of cold. Of hunger. Of the toxins of a whole history.

But her feet were held against his breastbone.

The last heat of his flesh was his last gift to her.

Let no love poem ever come to this threshold.

There is no place here for the inexact

praise of the easy graces and sensuality of the body.

There is only time for this merciless inventory:

Their death together in the winter of 1847.

Also what they suffered. How they lived.

And what there is between a man and woman.

And in which darkness it can best be proved.

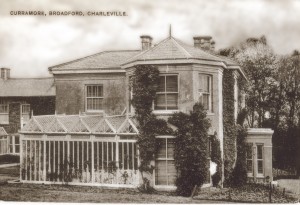

These lands of Killagholehane were granted in 1586 under the terms of the Plantation of Munster to an English family with the name of Anketell. The old era had come to an end and a new one would enfold. Diarmuid O’Sullivan (Dermot Sullivan) acquired these lands from John Anketell through a Deed of Mortgage in 1685. Brothers Jeremiah Sullivan and Francis Sullivan descendants of Dermot came to live here in the early 1800s, Jeremiah in Banemore and Francis in Glenview Lodge. Jeremiah’s son John J. built Curramore House in the mid 19th century and the estate was laid out with beautiful avenues and ornamental gardens. John J’s son Herbert known as the Minor Sullivan resided in Curramore House . Herbert was the resident magistrate and chairman of Broadford Co-operative Creamery. Curramore House was occupied by a small force of Republicans during the Civil War. At the approach of the Free State soldiers into County Limerick around August, 1922 they burned the beautiful mansion. Previous to this Herbert Sullivan had retired to Devonshire in England from whence his wife hailed. The estate was purchased by the Free State Government and divided into a number of smaller holdings.

Herbert was the resident magistrate and chairman of Broadford Co-operative Creamery. Curramore House was occupied by a small force of Republicans during the Civil War. At the approach of the Free State soldiers into County Limerick around August, 1922 they burned the beautiful mansion. Previous to this Herbert Sullivan had retired to Devonshire in England from whence his wife hailed. The estate was purchased by the Free State Government and divided into a number of smaller holdings.

”The Famine”

This district suffered severely from the famine of the 1840s An Gorta Mór. Many people died from hunger and fever. The following account was handed down to us and recorded in The Schools’ Manuscript Collection 1937/1938 which was initiated by the Irish Folklore Commission. A local man counted seven funerals on the one day going to this cemetery of Killagholehane. “It was the hinged coffins that were used to bring the corpses so that the coffins could be used again, the people could not afford to buy coffins.” The funeral procession came from the Knockacraig direction and the coffins were borne on shoulders along the old road and boreens to the Churchyard. The bodies were interred in the same grave.

”Mass Paths”

As you walk these trails you will be using some of the footpaths that were used by families each Sunday to get to Mass in Broadford. These paths were the shortest route by foot across hills and valleys to get to the village. The routes were used in the 19th century and late into the 20th century.

”The Church of Killagholehane”

Legend tells us that a woman of the Ui Liathain family wished to honour God by building a Church and prayed for a sign that would indicate where the church should be built. Her prayer was answered….. One summer night the surrounding countryside was covered with snow…. except for one small field. The woman took this as a sign and there the church was built. It was dedicated to Our Lady of the Snows. The present church dates from the 15th century. Within the burial ground adjacent to the Church is a Republican Plot and the headstone commemorates local men who died in the War of Independence and are interred there.

”Gleann na gCapall”

This glen dates from The Ice Age when a glacier gorged out this valley. However in folklore, a woman out saving hay one very warm day grew thirsty and went into Killagholehane church and drank some of the consecrated wine. For this sacrilege she was turned into a horse and as such continues to haunt Gleann na gCapall.

TEN THINGS TO DO IN THE BROADFORD ASHFORD AREA.

- Walk the Broadford Ashford Walking Trails and discover this majestic landscape of rolling hills, open farmland and forest paths. Enjoy the flora and fauna and historical points of interest.

- Visit the historical Mass Rock in Ashford and the nearby Glenquin Castle

- Broadford arboretum is not to be missed which includes twenty six native species of trees.

- Experience Seisún a great traditional night of music, song and dance during July and August. Let your holiday coincide with a local festival.

- Visit the 15th century Killagholehane church ruins and be intrigued by its history.

- Extend your visit and walk or cycle the Limerick Greenway with access point at Rathkeale, Newcastle West and Barnagh Gardens. Climb Knockfierna and pass the deserted famine cottages as you ascend.

- Call to the pubs in Ashford, Broadford and Ratheenagh and enjoy the ‘craic’

- During your holiday explore West Limerick, visit Newcastle West, Limerick’s largest town with its Desmond Castle, boutiques and restaurants. Discover the Irish Palatine (German) museum, visit Adare village with its thatched cottages and restaurants and don’t forget Foynes Flying Boat and Maritime Museum.

- Fit in a local Gaelic hurling or football match or play your own game of golf in Adare, Charleville or Newcastle West.

- The children will love the new playground in Broadford.

The above list is just a sample, discover many more. Enjoy!

Directions Limerick to Ashford:Take N21 from Limerick signposted Tralee/ Killarney. Enter Adare. Entering Newcastle West at the first roundabout take 1st exit, at the second roundabout take 2nd exit onto R522 signposted Dromcollogher. After 7km turn right signposted for Broadford. Enter Broadford.Turn right on entering Broadford and go to the end of the village and take the Abbeyfeale road R515. Enter Ashford after 6km.

Cork to Ashford:Take N20 from Cork signposted Mallow. Approaching Mallow at roundabout take 1st exit onto N72 signposted Killarney. After 13km turn right onto R576 signposted Kanturk. Enter Kanturk and take R579 road signposted Newcastlewest . Continue for 23km and enter Broadford.Turn left on entering Broadford and take the Abbeyfeale road R515. Enter Ashford after 6km.

Limerick to Broadford :Take N21 from Limerick signposted Tralee/ Killarney. Enter Adare. Entering Newcastle West at the first roundabout take 1st exit, at the second roundabout take 2nd exit onto R522 signposted Dromcollogher. After 7km turn right signposted for Broadford. Enter Broadford.

Cork to Broadford :Take N20 from Cork signposted Mallow. Approaching Mallow at roundabout take 1st exit onto N72 signposted Killarney. After 13km turn right onto R576 signposted Kanturk. Enter Kanturk and take R579 road signposted Newcastlewest . Continue for 23km and enter Broadford

Accomodation/Restaurants in the Broadford/Ashford area